It is the 70th anniversary of the victory in Wimbledon, on July 3, 1953, of the American Vic Seixas, after beating the Danish Kurt Nielsen in the final in the center of the All England Club. Champion of the first edition of the Conde de Godó Trophy two weeks earlier, Elias Victor ‘Vic’ Seixas, who will turn 100 during the US Open, is the oldest living Grand Slam champion.

Vic Seixas, who had been convinced by Jaime Bartrolí to play the tournament that inaugurated the new headquarters in Pedralbes of the Real Club de Tenis Barcelona-1899, traveled from Barcelona to London to have a few days to adapt to the game on grass courts. Wimbledon was a tournament that suited his game. He had been a semifinalist in his debut in 1950, in which he was beaten by compatriot Budge Patty, and a quarterfinalist in 1952 against Herbie Flam.

On his way to the 1953 final, Seixas knocked out Britain’s Robert Lee, Poland’s Wladyslaw Skonecki, Belgium’s Philippe Washer, and Australia’s George Worthington, Lew Hoad and Mervyn Rose in succession. Seixas had been seeded second at Wimbledon, in a season in which he had reached the semifinals at the Australian Open and the final at Roland Garros, both times defeated by Ken Rosewall.

When Kurt Nielsen staged the big upset of the tournament by eliminating Rosewall in the quarterfinals, Seixas thought it was his moment. “I remember that I thought that this was an opportunity to win at Wimbledon, something that was the tournament that we all dreamed of winning. Fortunately, I knew how to withstand the pressure and take that marvelous trophy home with me”, recalled Seixas during his visit to Barcelona in 2002 for the 50th edition of the Conde de Godó Trophy. “For the win I was given a £25 voucher to buy something tennis related at Lillywhites in Picaddilly. I bought myself a jersey, ”he added.

Victor Seixas was born in the Overbrook Park neighborhood of Philadelphia on August 30, 1923. His father, Victor Elias Sr, was born in Brazil, into a Portuguese Sephardic Jewish family. His mother, Anna Victoria Moon, was a descendant of Irish emigrants. Seixas grew up a few meters from a tennis club of which his father was a member and amateur player. Although his great sporting passion was baseball, and he did not miss any Phillies game, since he was little he showed his skills with the racket.

At the age of six, he started rallying with his father and it only took him a month to defeat him in a match. He was the valedictorian at William Penn Charter School and the leader of the tennis team at the University of North Carolina. In 1938 and 1939, Vic was able to witness live the two Davis Cup Challenge Rounds between the United States and Australia, played respectively at the Germatown Cricket Club and at the Merion Cricket Club in Philadelphia. It was then that he made the decision to abandon baseball since he could not combine both sports, since the oval sports stadium was on the other side of the city.

Seeing Donald Budge, Bobby Riggs, Frank Parker, Jack Kramer, John Bromwich, Adrian Qvist and Gene Mako in action was what convinced Vic Seixas to work hard and try to be a good amateur tennis player. He was amazed at the discipline of the Aussies, all of them athletes, and he began to train as if his life depended on it. Thanks to this effort, Seixas developed enormous power in his lower body that was key in his progression.

In 1940, at the age of 17, Seixas played his first tournament, the Pennsylvania Championships, in which he reached the semifinals. Weeks later, he got an invitation to play his first US Open. He had never been to Forest Hills before and was impressed by the scale of the facility. He debuted with a victory against William T. Vogt and was the sensation in the second round against Frank Kovacks, the American with a Hungarian father who occupied the third position in the American ranking and who was known for his continuous eccentricities on the track.

Seixas won the first two sets and only Kovacks’ seniority allowed him to come out on top in five sets. “Everyone wondered where that kid from Philadelphia whose last name was so difficult to pronounce had come from,” Seixas recalls at that time. “They couldn’t believe that an unknown person, and also a rookie, had put Kovacks on the ropes,” he adds.

That was the beginning of a love affair for Seixas with the US Open, in which he competed in the individual event in 18 editions between 1940 and 1969. Only in 1943 and 1945, enrolled in the US Army during World War II, and Stationed as a fighter pilot in New Guinea and Tokyo, Seixas was not on the start list.

A good part of those years, Seixas spent more time helping his father in his plumbing business than on the training tracks. Until 1948, when he was selected to play in the Pan American Championships, Seixas did not compete outside the United States. In 1950, at the age of 27, and when he was already among the best players in the country, Seixas did not participate in a Slam outside the United States. Joined.

For the first time he went to Roland Garros, where he was defeated in the quarterfinals in five sets by Jaroslav Drobny. “He moved with astonishing speed. He had a very good cut backhand with which he changed rhythms and a very powerful serve that allowed him to go to the net with guarantees. He was a strong player in every sense of the word,” Drobny explained of him in an interview.

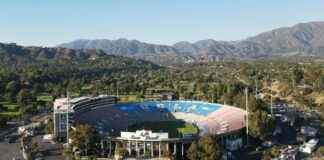

After winning the 1954 US Open against Rex Hartwig, Seixas had another great moment when together with Tony Trabert, Ham Richardson and Bill Talbert they snatched the silver salad bowl from the Australians (Hoad, Rosewall, Hartwig and Rose) in 1954 at the White Sydney City Stadium. Seixas won two of the decisive points, defeating Ken Rosewall in the second individual and prevailing in the double with Tony Trabert against Rosewall and Hoad.

Seixas remained an amateur as he did not receive interesting offers to enter the professional circuit. Late in his career, he worked as a stockbroker for Goldman Sachs and later ran a luxury West Virginia resort with golf legend Sam Snead. In 1970, he seemed the chosen one to direct the tennis club of the new Caesars Palace in Atlantic City, but the delay of the works prevented it. In 1971, Seixas was inducted into the Newport Tennis Hall of Fame.

Haunted by debts, largely generated by two divorces, and taking advantage of the rise in the price of silver, Seixas was forced to melt down a large part of his trophies. He just the precious Wimbledon trophy and a few others were left in his showcase. Things were still not working. He got a job as a bartender in a cafe and most of the customers didn’t know about his past. During Wimbledon, he always had the television on to watch the matches.

His friends had to help him when he could barely stand and was forced to use a wheelchair. Stan Smith, president of the Hall of Fame, got Adidas to give him a support contract. Five years ago, a group of friends launched a campaign online to raise funds to cover the hospitalization and medication costs that this living legend of the sport needs.

Last week, Seixas was still able to attend an interview requested on the occasion of the 70th anniversary of his victory at Wimbledon. “Since Federer has retired, I have stopped watching tennis,” was his analysis of the current tennis situation.