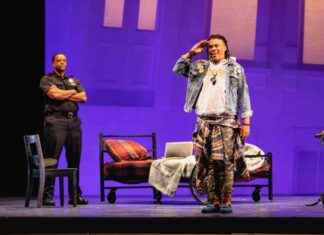

They are three decades of the difficult story of a white South African family with the profound transformations of their country as a backdrop: apartheid, the arrival of Mandela, change, corruption, disappointment… Or perhaps it is the story of South Africa with a family as a vehicle , the Swarts, farmers, through their deaths and their more than peculiar funerals over three decades. But in any case it is the great metaphor of a long unfulfilled promise, both in the leading family and in the country. A story titled The Promise (Asteroid Books/Les hores), which won the 2021 Booker Prize and which Damon Galgut (Pretoria, 1963) presented yesterday in Madrid.

A pessimistic Galgut about the present in South Africa: “Some time ago there was talk of the rainbow country and everyone felt happy, now they would laugh at you, the feeling is gone, unfortunately,” he says. And he stresses that the current president, Cyril Ramaphosa, is trying to change the disastrous years of Jacob Zuma, “but he has many political obstacles because many oppose him in his own party and also his approach is slow: he is a gentleman, but he is facing to gangsters, and you can’t negotiate with them, it doesn’t work like that.”

He confesses despite everything that the first idea for The promise was not to talk about South Africa but the very structure of the work. “At this point I’m fascinated by the passage of time and getting closer to the end, although I hope it’s not too close yet. I had a conversation with a friend about the successive funerals of his family and it seemed to me an interesting way of approaching a family, of looking at all its members through the lens of time. I didn’t initially plan to talk about South Africa, but with the books you sit for a long time and I saw that if I widened the window I could show South Africa, which has also undergone great changes. Even the title, which now seems central, came, he says, at the end, although in retrospect it seems the fairest: “The promise that the family makes to Salome is an addition and is born from the story of another friend whose mother, when she died, made promise that a piece of land would be given to the black woman who worked for her. The family promised, they didn’t and he kept reminding them.”

In that sense, he recalls that “a central theme for South African history is the question of who owns the land, who used to own it and who will in the future. Today the most radical party wants the return of the land to black people, implying that all whites are foreigners and do not belong to them. If it happened, they would leave and there would be an economic implosion.” It would be the icing on the cake in a country where, he points out, “the infrastructure in almost every field is falling apart, there are blackouts for six to eight hours every day. Rail service is in collapse. And the roads. We are in serious trouble right now.”

In his novel, in fact, the country evolves from hope to despair. “I don’t do a decade-by-decade political analysis like Nadine Gordimer would have done, I try to convey a feeling, a flavor of those four moments. And if you do it precisely, it is clear that the trajectory of the country is going down. There was enormous potential in the 1990s and a great will on the part of many South Africans to make a new country and make it work. Politicians have failed. The African National Congress rules, a party so powerful that there was no chance of it losing. They had the chance to change the country, but there was enormous corruption and incompetence.”

And more seriously, he adds, “South Africa has not yet learned to live together. In the nineties there was a will to overcome racial divisions. But if political power changed hands, economic power did not. Today the new barriers are of class, but they follow very much the racial ones. There are interactions inside the classes, but not outside. And most of the people are working class or homeless, and most of them black. A fundamental economic change is needed for there to be a social one, but there is no plan.”