The first time the writer Amador Guallar touched the rough and rough skin of a black rhino with his hand, he was paralyzed and a bittersweet feeling came over him. “It was like touching a world that had almost disappeared”, he remembers. That day in the Dinokeng nature reserve, in South Africa, his feeling of counting down, of being in front of the last days of an endangered species – according to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature, there are only 3,142 specimens of this species left, the stage before its disappearance – it was not an isolated emergency. “If nothing is done to stop the decline of African wildlife and conserve what is left, I think we will be the last human generation to see animals truly in the wild. We will be the last to experience the untamed world and the earthly paradise we live in,” he explains.

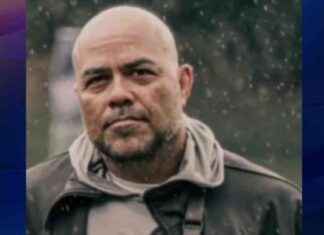

After covering several conflicts in the world as a reporter, Guallar has spent several months touring the natural paradises of Africa to raise awareness of the alarming decline in animals on the continent. As a result of these trips, he publishes the book Los últimos dÃas del Ãfrica salvaje (published by Diëresis), in which he reveals both the threats to nature and the work of those fighting to preserve the ecosystem. In a telephone conversation from l’Escala, where he is resting before his next coverage, the root of the problem is clear. “There are many factors behind the decline of African animals, but the human being is at the center. The increase in population and the lack of respect for the natural environment have caused this situation with almost no return – explains Guallar-. Climate change due to human action and the poaching of rhinoceros or elephants, but especially the subsistence linked to poverty, of those who hunt for food, has also led to this unsustainable situation”.

Nature conservation groups have been warning of the catastrophe for years. If a few years ago the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF, in its acronym in English) denounced that since 1970 more than 20,000 populations of mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles and fish have been reduced by 68 %, the death last week of Loonkito, the longest-lived lion in Africa at 19 years, killed by some Kenyan shepherds, shows the fragility of the current scenario. According to experts, with a population of just 20,000 lions in Africa, in just 10 or 15 years the kings of the African savannah will have disappeared in a state of freedom.

The natural context will make things worse. According to a recent study published in the journal Nature climate change, the worsening of the climate crisis will multiply the threat. After analyzing 49 studies, a team led by American biologist Briana Abrahms revealed that several climate-related phenomena that are increasingly common have increased conflict between wildlife and humans. “The biggest surprise – explains Abrahms – was how ubiquitous [this connection] is, whether in the ocean or on land, in the Arctic or in southern Africa, it is very widespread on a global scale” .

In the report, biostatistician Joseph Ogutu leads a comprehensive analysis of 39,000 human-wildlife conflicts between 1995 and 2016 in Kenyan nature reserves. While most cases are related to elephants, which destroy crops, they also recorded 4,500 incidents with apes and baboons, 2,400 with buffalo, 1,500 with hippos, 1,645 with lions and 925 with hyenas.

Although droughts have reduced the diet of some species and heat threatens the breeding seasons of others, Ogutu points to human expansion as a tipping point. “Wildlife and shepherds used to manage by being mobile and flexible.

But because the number of human beings has increased and the number of human settlements and infrastructures has grown, coexistence is becoming increasingly difficult. We really need more space for wildlife to live freely.”